Several years ago, I started a series of columns about storyline continuity at the Big Two, and how it had become a far bigger hindrance to good storytelling than an enhancement. With DC’s upcoming reboot, it seems like a good time to share those thoughts again. So, here goes, although I tweaked it a bit, removed then-topical references, and added passages that make me seem far smarter and precognitive than I really am. And if you’re one of the seven who read this the first time around, you have my undying gratitude. For enduring this twice.

***************************************************************************************************

Relatively few buyers knew or cared that there was a prior incarnation of The Flash not that many years prior.

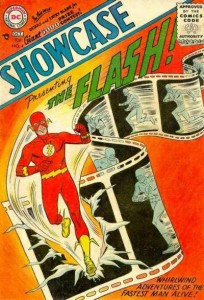

When Barry Allen was introduced as The Flash in 1956, most ten-year-olds who picked up Showcase #4 had no idea that there was ever another character called The Flash who was one of National Periodical’s mainstays during the previous decade. In fact, the previous series had only ended seven years earlier. But, comics by and large back then were children’s entertainment, and seven years is an eternity to a kid not much older than that. So unless they had a father or older brother who could make them aware of the original character, these kids were content to revel in the adventures of The Scarlet Speedster, who as far as they knew was the first character of his kind.

Until a few years later, at least, when writer Gardner Fox reintroduced Jay Garrick to a brand new audience in the now-infamous Flash #123. And with that, he felt compelled to explain how this older character could co-exist with the newer one, and in the process came up with the both loved and loathed concept of multiple Earths. By keeping the heroes of the forties in one world and the heroes of the then-current day in another, both could co-exist in separate but equal universes, go about their affairs, and never the twain shall meet.

Except, the story was so popular, the twain did meet. Again and again. Soon, Earth-hopping was as easy as crossing the street, and Earth-1 begat not only Earth-2, but Earth-3, and Earth-X, and so on. Future writers and editors at DC couldn’t resist continual inter-dimensional crossovers, and as time went on, the histories of the individual Earths got mixed up in the creators’ heads. Characters who were supposed to be from one Earth would pop up on another, with no explanation. To those trying to keep track of who’s who and where’s where, it became a dimensional accounting nightmare. The twain had gone and cwashed.

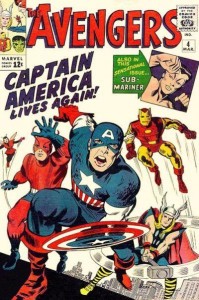

Over at Marvel, things thankfully remained a lot simpler. When Captain America was reintroduced in 1964, he was immediately explained to be the same Captain America from the forties. Not a new character in a new costume, but the same guy. This seemed to set a precedent at Marvel, who embraced their history rather than segregate it, that kept things much more cohesive.

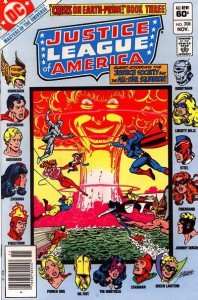

This had never been more apparent than in the fondly remembered Fantastic Four #25-#26, where The Thing battled The Hulk prior to the intervention of The Avengers. Not that it hadn’t been apparent before, but this story cemented the idea in readers’ minds that the Hulk, The Fantastic Four, and The Avengers all existed in one unified world. This wasn’t quite the case at DC; all of their Silver Age characters, as we now call them, were known to exist on what was now called Earth-1, but there wasn’t that feeling of unity within that one earth. Sure, the characters interacted in Justice League of America, but in Superman, for instance, the only other places that seemed to exist outside of Metropolis were Smallville. And The Phantom Zone. And Krypton. But no Gotham. No Coast City. These cities all sure existed in the same world, but they sure didn’t need to. It seemed that Superman of Earth-1 journeyed to Earth-2 more than he did to Keystone City of his own world.

DC had to spend a lot of creative energy keeping its dimensions straight, but it was kind of cool for awhile. And as the Marvel Universe expanded, editors tried to explain that Thor didn’t show up in The Avengers that month because he was in Asgard, or that the FF weren’t home when Iron Man called because they fighting Annihilus in The Negative Zone. And that was cool too. Editors realized that continuity was a neat storytelling device, because it added a sense of believability and realism to the stories. And believability was most definitely an issue when having to explain why there were two Supermen, who were different versions of the same guy, and two Flashes, who were two distinctly different people. And Marvel established early on that their stories took place in “our” world, or at least the New York of our world, so if The X-Men are off fighting for their lives on Asteroid M, they couldn’t possibly appear in another title the same month without an explanation.

This was a likely reaction from anyone trying to figure out pre-Crisis continuity. Or post, for that matter.

But somewhere along the line, something happened. Continuity went from being a tool to being a mandate. The cart was put before the horse. Continuity became King. Continuity became an ever-growing 800-pound gorilla that publishers had shackled themselves to, and it wasn’t quite so easy to tow around anymore. By the time the mid-eighties rolled around, DC readily admitted that they were all but crippled by this; old-time readers couldn’t make sense of things anymore, and new ones didn’t even want to try.

As everyone knows, the weapon DC devised to beat this beast into submission was the Crisis on Infinite Earths storyline. This was supposed to fix everything. And at first, Marv Wolfman’s story did. As best it could, anyway. But as everyone also knows, that didn’t last. More questions arose than were answered. And future creators didn’t adhere to the simplified universe. And before we all knew it, things were screwed up beyond understanding again. So DC tried it again, with Zero Hour. It was another great story, but it too left more questions than answers. Then-senior editor Mike Carlin later said that every time DC tried to fix things, they only made them worse in the end. The solution to that challenge was the idea of Hypertime, a concept that was essentially made to be the root cause of all glitches in DC continuity. If, say, Legion of Superheroes history was too difficult to sort out, well then, blame it on Hypertime. If you can’t find an explanation, then find a scapegoat instead, and move on. At the time, this honestly seemed to be the best solution, rather than trying fix after fix after fix. That rug sure looks good over that big hole in the floor, but don’t try to walk on it.

But years later, then-current senior editor Dan DiDio just said that the Hypertime concept had been abandoned and was no longer a story device in the DCU. Ookay. So where did that leave DC’s continuity freaks, who insist on some kind of reasonable way to explain, say, Hawkman’s origin? It left them nowhere. DC had gone from trying to provide reasonable answers to such questions, to providing less reasonable ones, to providing none at all.

But it brought up a far better question, though, and a much farther-reaching one: how long are fans and publishers supposed to remain slaves to continuity? What other medium has even tried? It’s not that it can’t work; there’s valid continuity in, say, the Star Wars universe, but that’s only six films. A long-running TV franchise like Star Trek has been able to pretty much able to keep it all in check. But Marvel and DC have been around for nearly seventy years, and they have tried valiantly to make to tie their countless stories by countless more creators into a sort of communicable history, but face it: it just can’t work anymore. It’s too big, and too disparate. There are too many titles by different generations of creators. When the DC and Marvel Universes were in their adolescence, history was definable. Now, it’s like trying to describe the workings of nanotechnology. Just try explaining the whole multiple Earths concept or the history of The X-Men to a civilian in 30,000 words or less. You’ll lose them after thirty.

So what has to happen? I will tell you, but you already know. You’re on the brink of seeing it happen, at least at DC.

Continuity must die. DC has figured out that the 800 pound gorilla must be brought down, and that’s exactly what they’re doing. More next week.

****************************************************************************************

So yeah; I called for a company-wide reboot back in 2005. No, I’m not gloating. I’m just glad DC finally listened . . . 😉

JJ

The thing is, I don’t equate a company-wide reboot to an adjustment in how they are handling continuity. If DC handles it the same way they’ve always done, we’ll be right back into “wait, which Superman is this?” inside of a year.

They can relaunch all they want, but if the editorial perspective doesn’t change, then in the long run it becomes a giant SO WHAT, in my opinion.

But, things really AREN’T changing. The Batman titles and Green Lantern titles will still be the same. Gail Simone on her twitter feed promises that the Secret Six will be intact (including red-headed lesbians!!! Hey, I’m just repeating what she said). And, one of them is Knockout, who was a Superboy foe….oh, wait, things CAN’T be the same, since this WON’T be the same Superboy….

…see, the problem is, not with a reboot, but with a PARTIAL reboot.

I think that DC is trying as usual to clean things up and make then more clear. But since this is not a mini-series or “event” I think that it makes it harder to push through.

This is an across the board “restart” of the DCU. But unfortunatly they are not restarting all from go. They are trying to drag carry overs into what is suppose to be a new universe.

Time will tell if this works. But I think that we all know that this will most likely work as well as all the other attempts to reset a comic book reality.

DC has acknowledged that elements of past continuity remain intact; the Death of Superman and The Killing Joke were two examples that they cited. But I don’t think they’re going to spend much if any time explaining the hows and whys. It’s not so much that DC is disgarding old continuity as much as they’re just leaving it behind and finally moving forward, taking with them only whatever they can carry.

Like Wayne says, time will tell, but DC genuinely seems to be trying to put the horse back in front of the cart again. The 800 lb gorilla-style continuity is dead, and in its place we’re apparently going to get a cute and cuddly baby chimp. How spoiled and overfed it gets is what’s to be determined.

Gorilla Grodd, 800 pounds. ‘Nuff said! (Oops, that’s Marvel).