“Art takes time, time is money,

Money’s scarce, and that ain’t funny.”

Low Budget, from The Kinks’ Low Budget, © 1979. Lyrics by Ray Davies

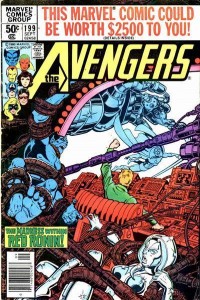

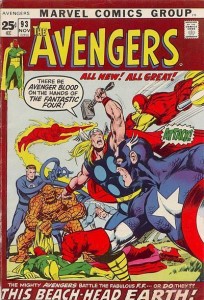

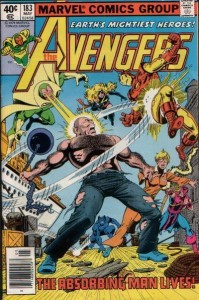

When that song was released, it was a time of record inflation, led the way by oil and gas prices but quickly followed by ever-increasing prices in just about everything we bought. And yes, that included comic books, which at the time had just risen to a staggering, gasp, forty cents.

Forty cents; a once-thinkable quadrupling of the price that comics had stood at for decades, all while the story page count had dwindled to a mere seventeen pages over the same time. Of course, we didn’t know how good we had it; since 1979, the price of a standard comic has increased another tenfold.

The seventeen-page story count had long been viewed as a kind of unspoken and untouchable limit on the low end that dared not be breached. It was the publisher’s own version of glass that was to be broken in the event of an emergency; the limit could be breached, if necessary, but it would take an extreme circumstance to do so. To reduce that page count by even one page would put the story content of a comic at a mere 50%, and therefore invite undesirable accusations that comics were half full of advertising; accusations that wouldn’t quite be true, when accounting for letters and editorial pages, but hard to refute regardless.

The ten cent price increase was unwelcome, as were the large banners at the top of each cover, but it was worth the five additional story pages.

The ten cent price increase was unwelcome, period. The price and page count dropped the following month.

When Marvel found it time to raise prices again the following year, in 1980, they opted to raise them a full ten cents; an unprecedented increase, but one that allowed them to circumvent the difficult idea of further reducing story pages and instead add a full five pages of story content to each comic. Marvel had unsuccessfully tried a similar trick several years earlier, but this time it stuck; apparently another dime was a little easier to part with in 1980 than it was in 1971.

And the 22-page story count became the norm and largely remained so until very recently, when DC heavily promoted their Drawing The Line campaign, which reduced the price of most of their comics by one dollar but also reducing the story page count from 22 to 20.

Like a four dollar gallon of gas, apparently a four dollar comic book is also enough to inspire a serious call to action. But where expensive gasoline inspires alternative solutions like other fuel sources, more fuel efficient vehicles, and modified driving habits, expensive comics just inspired . . . making them cheaper.

Now, no one will argue that making something less expensive in and of itself is a bad thing. It’s the measures that are taken to bring about this cost reduction that can be of concern. And in the case of comic books, holding the line at $2.99 isn’t necessarily a good thing. And just exactly why not, you ask?

I will tell you.

When inflation was running rampant in the late 70s, nothing mattered more to manufacturers than doing whatever they could to hold costs down so that consumers would continue to buy their products. And this was largely done by sacrificing those same products; page counts were reduced, fewer cookies were packaged in the box, fewer chips in the bag, less ice cream in the carton. Unproven materials were used to build homes. Substandard manufacturing practices were used to build cars.

Manufacturers, in an attempt to keep their products cheap, made their products . . . cheap.

Nothing was more aggravating than buying a bag of potato chips that didn’t seem to last quite as long as it used to. Except maybe for driving a car that rattled and clunked down the road, if it didn’t break down entirely. And drafty windows in a new house were inexcusable, but it happened.

So maybe reducing a page count to 20 doesn’t seem so bad, if it means literally saving a buck. But how about if it drops to 18? What about if it goes back to 17? And what about when the price of a standard comic book inevitably goes back up, as it will? Because cheapening comic books won’t prevent price increases; it will just stall them for awhile. What’s going to happen when DC stops holding the line that they’ve drawn, and starts to toe it?

It’s only a matter of time before we’re paying $3.99 for a twenty page story, putting us in a worse position than we were when DC decided that the line should be held. Making comics cheaper is a laudable goal, but making them cheap is not.

Especially when it’s a medium still trying to win over mass acceptance.

JJ

Back in the late 1990s, I wrote an article called the “76 cent solution” which argued that the cost of a $0.20 comic from 1972 should only cost about 76 cents at the time of the article’s writing if it had merely kept up with overall inflation. Today, that same comic would clock in at $1.03, taking inflation into account.

So why are we arguing about whether it’s possible or advisable to keep the line at four times that price? One big clue comes from looking at the ad pages inside a 1972 comic and comparing them against a current Marvel one. The 1972 comic is almost entirely populated by paid (and generally smaller) ads, whereas most current Marvel and DC comics feature only full page ads with “house ads” taking up a great deal of the salable space. In short, the $4 comic of today needs to be supported by its actual street price, whereas the $0.20 comic of 1972 was largely supported by its advertisers.

A large part of the increase is also due to better creator compensation and higher production values. But to go back on either of these is undesirable; the return to a literal four-color palette, for example, would only be another form of cheapening the product, and I don’t think anyone wants to see any of the gains made by creators over the years curtailed.

Regarding advertising, some have suggested over the years actually ADDING 8 or 16 pages, all ads, to a standard comic book, to hold the price down and preserve the story page count. This is actually closer to the business model for many periodical magazines, but I wonder with so many publications having difficulty filling advertising space nowadays, this would probably no longer work.

Maybe that’s why comics feature so many inhouse ads, come to think of it.

Sadly, most of the people buying comics…are the one’s buying them now, thus comics ARE the only home of advertisement ON comics.

And, the slow loss of pages….makes waiting past a month for issues even more embarassing.

So we should just suck it up and pay four bucks a book now because there’s the off chance that at some undetermined time in the future books will be $4 anyway at only 20 pages?

That seems rather defeatish to me, and I’m not so sure I agree.

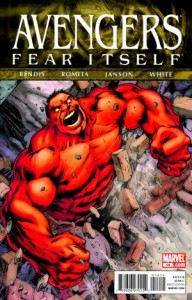

I applaud DC for trying something. Yeah, it may not be to everybody’s tastes, but neither is a $4 comic. I’m hoping that their new initiative and price point makes a difference and turns the tide, but I’m also a realist. That doesn’t mean that I’m going to shoot myself in the foot and support $4 comics at the same time, however. Marvel has not gotten a dime of my money since they forged ahead with $4 books. Their loss has been DC’s, and Image’s, and Dark Horse’s, and IDW’s gain.

It’s not an off-chance; it’s a relative certainty with the only unknown being how long it will take. History has proven it. Sure, I’ll enjoy it while it lasts, however long that is, but I can just hear future fandom’s teeth gnashing now when those comics break the $3 barrier again.

At Comic-Con, DC admitted that the Drawing the Line campaign failed; it yielded temporary sales increases that immediately began dwindling again. But, simply raising the prices back to their old level would have been disastrous, so they realized they had to try something else, a something else that became the upcoming relaunch. I don’t know why they didn’t think of simply trying to make their comics better in the first place; readers just might have been willing to pay $3.99 for a Geoff Johns / Jim Lee Justice League comic.

When the prices start going up again, and they will, at least we (hopefully) will be getting a better product than what we were when the prices dropped.